The mental shift that should happen around mile 3-4 on the treadmill represents one of the most critical psychological transitions in distance running, yet it remains vastly underexplored in fitness literature. This window-roughly 20 to 35 minutes into a moderate-pace run-marks the point where your body completes its initial metabolic adjustments and your mind must either settle into a sustainable rhythm or begin fighting against itself. Understanding this transition can mean the difference between a run that feels like an endless slog and one that transforms into a genuinely meditative, even enjoyable experience. Most runners, particularly those training indoors, recognize this phase instinctively even if they cannot articulate it. The first two miles often feel effortful as your cardiovascular system ramps up, your muscles warm, and your breathing finds its pattern.

But somewhere around that third mile marker, something shifts. Your perceived exertion may actually decrease despite maintaining the same pace. Your thoughts, previously fixated on physical discomfort, begin to drift. This is the physiological gateway many refer to as the “second wind,” though the psychological components are equally significant and deserve dedicated attention. By the end of this article, you will understand the science behind this mental shift, learn specific techniques to facilitate and harness it, and develop strategies to make those middle treadmill miles your most productive training time rather than a mental endurance test. Whether you are training for a marathon, working on cardiovascular health, or simply trying to make your daily runs more bearable, mastering this transition fundamentally changes your relationship with indoor running.

Table of Contents

- Why Does a Mental Shift Happen Around Mile 3-4 on the Treadmill?

- The Psychology of Treadmill Running and Mental Fatigue

- Recognizing the Signs of Mental Transition During Your Run

- Techniques to Facilitate the Mental Shift on the Treadmill

- Common Mental Barriers That Block the Treadmill Running Transition

- The Role of Breathing in Treadmill Mental Shifts

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Does a Mental Shift Happen Around Mile 3-4 on the Treadmill?

The mental shift occurring around mile 3-4 on the treadmill corresponds directly to measurable physiological changes that take approximately 15 to 30 minutes to fully manifest during aerobic exercise. During this window, your body completes the transition from primarily anaerobic energy production to a more efficient aerobic metabolism. Glycogen stores in your muscles begin releasing energy more smoothly, your capillaries dilate fully to optimize blood flow, and your core temperature stabilizes at an elevated but sustainable level. These changes collectively reduce the physical stress signals your brain receives, creating space for a psychological transition.

The phenomenon relates closely to what exercise scientists call the “steady state” of cardiovascular exercise. Before reaching this state, your body works through what researchers term the “oxygen deficit-“that initial period where oxygen demand exceeds supply as your systems ramp up. This deficit creates the labored breathing and heavy legs most runners experience in their first mile or two. Once your aerobic system catches up and oxygen supply matches demand, the subjective experience of exercise changes dramatically. Heart rate stabilizes, breathing becomes rhythmic rather than labored, and the acute discomfort that dominated your attention begins to fade into background sensation.

- The body takes 12-25 minutes to reach true aerobic steady state, corresponding roughly to mile 3 for most recreational runners

- Endorphin release typically begins around the 20-minute mark and continues building throughout sustained aerobic activity

- Core body temperature stabilizes approximately 15-20 minutes into exercise, reducing thermoregulatory stress on the brain

- Blood lactate levels, initially elevated during the oxygen deficit period, begin clearing more efficiently as aerobic metabolism dominates

The Psychology of Treadmill Running and Mental Fatigue

Treadmill running presents unique psychological challenges that make the mile 3-4 mental shift both more difficult to achieve and more rewarding once established. Unlike outdoor running, where varied terrain, scenery changes, and natural landmarks provide constant mental stimulation, the treadmill offers an unchanging visual and kinesthetic environment. This monotony taxes the brain’s attention systems differently, often leading to a phenomenon researchers call “attentional fatigue-“the mental exhaustion that comes from maintaining focus in a low-stimulation environment.

The treadmill’s digital displays compound this challenge. Constantly visible pace, distance, and time metrics encourage obsessive clock-watching, which research consistently shows increases perceived exertion and decreases enjoyment. Studies from the Sport and Exercise Psychology Research Laboratory at the University of Birmingham found that runners who frequently checked their metrics reported runs feeling up to 20% harder than those who covered or ignored the display. The mile 3-4 window represents the critical juncture where runners either learn to disengage from this metric fixation or remain trapped in a cycle of watching seconds tick by.

- Treadmill runners report significantly higher rates of boredom and perceived effort compared to outdoor runners covering identical distances

- The lack of proprioceptive variation (no hills, turns, or surface changes) reduces the brain’s processing demands but paradoxically increases mental fatigue

- Environmental temperature control, while physically comfortable, removes another variable that normally occupies mental bandwidth during outdoor runs

- The forced consistency of treadmill pace prevents the natural micro-variations in speed that occur unconsciously during outdoor running and help maintain mental engagement

Recognizing the Signs of Mental Transition During Your Run

Learning to recognize the onset of the mile 3-4 mental shift allows runners to consciously facilitate and deepen the transition rather than inadvertently fighting against it. The signs are subtle but consistent across most runners. Breathing that required conscious attention begins to feel automatic. The internal monologue shifts from statements about discomfort (“my legs feel heavy,” “this pace is hard”) to more neutral or even absent thought patterns.

Many runners describe a sensation of their body “taking over” while their mind becomes a quieter observer rather than an active manager. Physical awareness also changes during this transition period. Early-run hypersensitivity to every sensation-the tightness of your shoes, the temperature of the air, the impact through your joints-gives way to a more holistic body awareness. Individual discomforts integrate into a general sense of effort rather than demanding individual attention. This shift in body awareness parallels what mindfulness practitioners call “open monitoring-“a state of receptive attention without fixation on any particular stimulus.

- Breathing transitions from conscious effort to automatic rhythm, typically settling into a consistent stride-to-breath ratio

- The urge to check the display diminishes as external metrics become less relevant to the internal experience

- Peripheral awareness often increases as the intense focus on physical effort relaxes

- Time perception frequently shifts, with minutes beginning to pass more quickly or becoming difficult to estimate accurately

Techniques to Facilitate the Mental Shift on the Treadmill

Actively facilitating the mental shift around mile 3-4 requires deliberate practice and the right preparatory conditions. The most effective approach involves what sports psychologists call “attentional shifting-“the strategic movement of focus between internal and external cues throughout the run. During the first two miles, maintaining some external focus (music, a podcast, or visual engagement) can reduce the perceived effort of the oxygen deficit period. As you approach mile three, gradually shifting toward internal cues-your breathing rhythm, your footfall pattern, the cyclical motion of your legs-primes the brain for the meditative state that characterizes an effective mental shift.

Pace selection plays a crucial role in enabling this transition. Running too fast prevents the body from ever reaching true aerobic steady state, keeping stress hormones elevated and the mind locked in survival mode. Running too slowly may not generate sufficient physical engagement to occupy the restless parts of the brain that otherwise drift toward boredom. The optimal pace for achieving the mental shift typically falls in the moderate aerobic zone-roughly 65-75% of maximum heart rate for most runners-where the effort is sustainable but not trivial.

- Begin runs with loose external attention rather than intense focus, allowing the brain to warm up alongside the body

- Use the first two miles for “mental inventory-“acknowledging discomforts without judgment and trusting they will diminish

- Around mile 2.5, begin consciously softening your focus, releasing any tension in your jaw, shoulders, or hands

- Practice “sensation surfing-“moving attention sequentially through different body parts rather than fixating on any single area

Common Mental Barriers That Block the Treadmill Running Transition

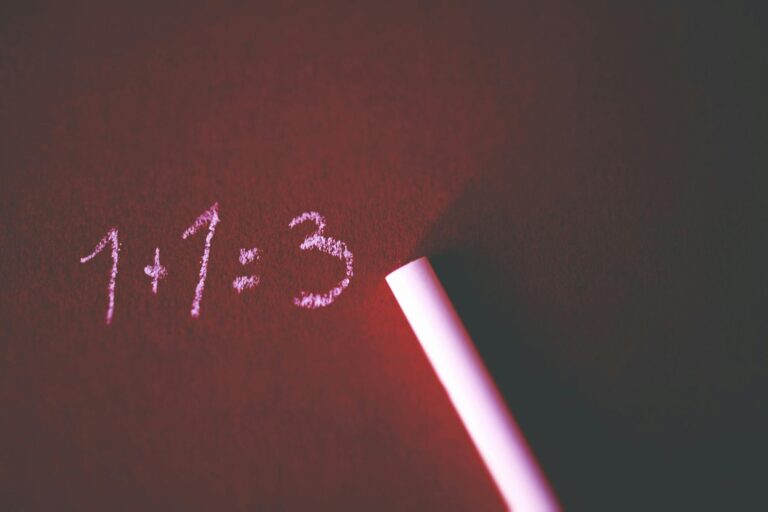

Several cognitive patterns consistently prevent runners from achieving the beneficial mental shift, keeping them locked in the effortful early-run mindset throughout their entire session. The most prevalent barrier is anticipatory thinking-the habit of mentally projecting forward to the end of the run, calculating remaining distance, or bargaining with yourself about when you might stop. This future-oriented attention pattern directly conflicts with the present-moment awareness necessary for the mental shift to occur. Each time you think “only two more miles,” you pull yourself out of the flow state you are trying to enter.

Another significant barrier is what researchers term “somatic hypervigilance-“an excessive attention to physical sensations that interprets normal exercise discomfort as threatening or problematic. Runners experiencing this pattern may notice their elevated heart rate and interpret it as distress rather than appropriate physiological response. They feel the burn of working muscles and catastrophize about injury or inadequacy. This hypervigilance keeps the threat-detection centers of the brain activated, flooding the system with stress hormones that preclude the relaxed focus of the post-shift state.

- Clock-watching creates a “watched pot” effect where time seems to pass more slowly the more attention you pay to it

- Comparison thinking, especially when running near others in a gym, generates performance anxiety incompatible with flow states

- Rigid pace expectations prevent the organic rhythm adjustments that help the body find its sustainable groove

- Physical perfectionism-constantly adjusting form, posture, or stride-maintains the analytical mindset that blocks the shift

The Role of Breathing in Treadmill Mental Shifts

Breathing serves as the primary bridge between the physical and mental aspects of the mile 3-4 transition, making it the most effective tool for actively facilitating the shift. During the oxygen deficit period of early running, breathing is necessarily reactive-your body gasps for the oxygen it needs, and conscious breathing control is difficult or counterproductive. Once aerobic steady state establishes, however, breathing can become a powerful anchor for attention, providing a rhythmic focus that occupies the mind without generating additional stress. The most effective breathing pattern for facilitating the mental shift involves synchronizing breath with stride at a consistent ratio.

Common patterns include 3:3 (three steps per inhale, three per exhale) for easy runs or 2:2 for more moderate efforts. This synchronization creates a metronome-like rhythm that the brain can follow without active management. Research from the Journal of Sports Sciences found that runners using synchronized breathing patterns reported lower perceived exertion and greater enjoyment compared to those breathing arrhythmically, even at identical paces. The rhythm essentially gives the mind something to do that requires minimal cognitive resources while preventing it from wandering into counterproductive thought patterns.

How to Prepare

- **Set your environment intentionally before starting.** Choose your entertainment in advance-whether music, a podcast, or nothing at all-and commit to it for the full run. Eliminating the option to constantly seek new stimulation removes a significant source of mental distraction. If using audio, select content appropriate for the mental state you want to achieve: upbeat music for the early miles, perhaps transitioning to something more ambient as you approach the shift window.

- **Establish your pace based on conversation ability, not arbitrary numbers.** Before your run, determine a pace at which you could speak in complete sentences but would not want to hold a lengthy conversation. This self-selected moderate pace almost always corresponds to the aerobic zone optimal for achieving the mental shift. Trust your body’s feedback over the display’s numbers.

- **Complete a proper warm-up that prepares both body and mind.** Walk for two to three minutes, then gradually increase to your running pace over another two to three minutes. This extended warm-up shortens the oxygen deficit period, meaning you reach steady state-and the potential for mental shift-sooner in your actual running time.

- **Set your display preferences before starting.** Either cover the metrics entirely, switch to a minimal display showing only essential information, or commit to checking only at predetermined intervals. Making this decision before you start removes the temptation to bargain with yourself mid-run.

- **Perform a brief mental reset at the start.** Take three deep breaths, consciously release tension from your shoulders and jaw, and set a simple intention such as “settle into the run” or “find my rhythm.” This brief ritual signals to your brain that the run is a distinct experience from whatever preceded it, facilitating the state change you are seeking.

How to Apply This

- **Use the first two miles as a physical and mental warm-up.** Accept that these miles will feel harder than what follows. Rather than fighting this reality, use the time to systematically scan your body, noting areas of tension or discomfort without trying to immediately fix them. This acceptance practice prepares you to release the monitoring mindset as you approach mile three.

- **Introduce a transition cue at mile 2.5.** This might be a specific song that signals the shift, a physical action like shaking out your hands, or simply a verbal cue you say to yourself. The cue serves as a behavioral anchor, training your brain to associate this signal with the release into a different mental state.

- **Shift your attention from external to internal as you pass mile three.** Begin focusing on the rhythm of your breathing, the cyclical pattern of your footsteps, or the general sense of motion through space. If your mind wanders to external concerns-the remaining distance, your pace, what you will do after the run-gently redirect it back to these internal rhythms without self-criticism.

- **Maintain the shifted state by riding the rhythm rather than managing it.** Once the transition occurs, your primary job becomes staying out of your own way. Resist the urge to check the display frequently, to analyze your form, or to plan the remainder of your day. Trust that your body knows how to run and allow your mind to simply accompany it.

Expert Tips

- **Vary your treadmill incline by 0.5-1% every mile.** This tiny variation provides just enough novelty to prevent complete monotony while remaining subtle enough not to disrupt your rhythm. The slight changes in muscle recruitment also help prevent the repetitive strain that accumulates during perfectly flat treadmill running.

- **Position yourself facing away from gym mirrors if possible.** Watching yourself run maintains self-conscious analytical attention that conflicts with the flow state you are trying to achieve. If you cannot avoid mirrors, practice softening your gaze so you are looking through rather than at your reflection.

- **Save your most engaging content for the first two miles, then transition to less demanding audio.** The early miles benefit from distraction as you work through the oxygen deficit. The later miles benefit from space-ambient music, nature sounds, or silence allow the mental shift to deepen in ways that podcasts or complex music cannot.

- **Practice the mental shift during shorter runs before expecting it in longer ones.** A runner who cannot settle into rhythm during a three-mile run will struggle to find it during a seven-mile session. Use your shorter training runs as explicit practice for the psychological skills that longer runs require.

- **Track subjective measures alongside objective ones.** After your run, note how you felt at miles two, four, and six. Over time, these subjective records reveal patterns-certain paces, times of day, or pre-run routines that consistently produce better mental states. This self-knowledge becomes more valuable than any training plan.

Conclusion

The mental shift that should happen around mile 3-4 on the treadmill is not merely a pleasant bonus of sustained running but a trainable skill that fundamentally transforms the indoor running experience. By understanding the physiological underpinnings of this transition-the resolution of oxygen deficit, the onset of aerobic steady state, the gradual release of endorphins-runners gain access to concrete strategies for facilitating and deepening the shift. The techniques outlined here, from strategic attention management to breathing synchronization to environmental preparation, provide a practical toolkit for converting the notorious monotony of treadmill running into an opportunity for genuine flow states. Mastering this transition pays dividends that extend well beyond any single run.

Runners who consistently achieve the mile 3-4 mental shift report greater enjoyment of their training, improved adherence to their running programs, and often faster improvement in their overall fitness. They also develop psychological skills-attention management, present-moment awareness, acceptance of discomfort-that transfer to challenges far beyond the gym. Your next treadmill run offers an opportunity to practice these skills. Rather than simply enduring the miles, approach them as a chance to explore the fascinating intersection of physiology and psychology that makes distance running one of the most accessible paths to altered states of consciousness available to humans.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.

Related Reading

- What Experienced Runners Feel During a Steady 6-Mile Treadmill Run

- How a 5-6 Mile Treadmill Run Should Feel for Longevity and Injury Prevention

- The “Sweet Spot” Feeling Every 5-6 Mile Treadmill Runner Should Reach

- The Physical and Mental Signals of a Healthy 6-Mile Treadmill Run

- Signs Your Treadmill Pace Is Perfect for a 5-6 Mile Run